Historic urban cores in various towns and cities in United States and across the world have traditionally used the five senses to create memorable experiences. In the first half of the twentieth century, places could be recognized very easily by smells resulting from patterns of activities along streets. Newer developments in cities such as Las Vegas are building on this great tradition.

In Europe and older cities and towns in United States, bakeries were typically located in the town centers. Baking created streets with lingering smells of sweet dough and jams, followed by the excited clamor of families returning home to feast. Washday involved smells of heat, detergent and moisture, followed by the smell of ironing – all intensified when such work was performed by larger groups of women sharing facilities and equipment.

Smell is powerful. Research indicates that smell stimulates emotional or motivational arousal, whereas visual experience is more likely to involve thought and cognition. Odors affect us on a physical, psychological and social level (Classen 1994). Designers and planners have the opportunity to create memorable and revealing urban experiences for people through thinking about their projects through non-visual terms, conditions and outcomes. As an example of multi-sensorial city wayfinding, Madurai challenges designers to comprehend the city in an emotional and visceral way – not a rational, information and consumer-based understanding typical of western cities.

Madurai, India

Background

The sacred city of Madurai is located in the southern Indian peninsula and is a major religious site for Hindu celebration. The city is organized around a central temple complex. All roads lead to religious sites of one kind or another. Up to 25,000 people a day, mostly religious tourists, pass through the temple complex on a given day.

The city’s rhythm, culture and commerce are reflective of the ever-present religious functions in the city that spill out onto the streets. Temple incense, oils, coconuts, camphor, flowers for offerings and other scented religious elements are readily available for purchase from street vendors at open air stalls. Temple ceremonies are multi-sensorial experiences. They include “a plethora of sense impressions as one enters the temple: the images of the deities, the smell of the incense, the touch of the priest, the sound of the temple bells and finally the taste of the Prasad( Drahos 2011).”

During regular days, the City is bustling with activity. All the major commercial streets are shared roadways with multiple modes of travel that include vehicles, bicycles, auto rickshaws, and pedestrians. The specific design of the retail stalls, especially with regards to the engagement of the wares with the street edge, the hawking of the wares, the use of colors and unconventional use of shop signs create a unique multisensory experience. The intensity of outdoor use and the accompanying sensorial experience increases as on moves towards the city core. The streets immediately adjacent and leading to the temple are imbued with scents of flowers, incense and other materials such as sandalwood. Similarly, paving materials and patterns change and are discernible to people wearing shoes or barefoot. The paths inside and immediately next to the temple complex are made up of cobbled stones. Finally, the set of three gateways elements (gopurams) and the 153-foot high gopuram on the sanctum sanctorum provide residents and visitors with a strong set of visual markers that help orient oneself in any part of the city.

During religious festivals held throughout the year, the city becomes charged with the smells and sounds of celebration. During the Chithirai Festival in particular, the entire city is a place for the religious experience, with the sounds, smells, and visual celebration enveloping the city. Madurai becomes navigable and known to people through overlapping pungent scents and the sound of marching drummers and temple bells.

As a wayfinding inspiration, we can extrapolate Madurai’s experience to make sensory-enabling design concepts that can potentially be applied to cities here in United States.

Lessons Learned

Potential Benefits:

- Brings a fresh, vibrant understanding of the city to people.

- Can be a boon to merchants without access to technology or traditional forms of advertising to attract customers. For example, food markets found across the developing world rely on smells to lure people in and make their location known. Street buskers and musicians can set up where sound travels well to attract more onlookers.

- Provides a sensualized experience of place – a nice compliment to information-centric wayfinding (signage) and mobile device technology that depends on the internet.

Potential Issues:

- Lack of support: There is cultural resistance, administrative barriers or misunderstanding regarding the use of non-traditional wayfinding approaches.

- Environmental factors: Environmental factors (wind, temperature, ambient noise, cleanliness, etc.) can impact the effectiveness of multi-sensorial wayfinding more than it does traditional or electronic wayfinding.

New York City, New York

Background

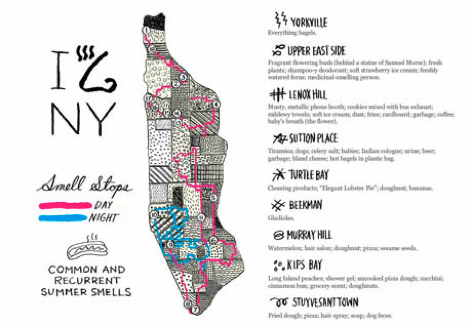

Jason Logan in an Op-Art piece in the New York Times (August 29, 2009) explored and documented the intended and unintended olfactory experiences of New York in summer. Titled the “Scents of the City,” Logan talks about how “New York secretes its fullest range of smells in the summer; disgusting or enticing, delicate or overpowering, they are liberated by the heat. So one sweltering weekend, I set out to navigate the city by nose. As my nostrils led me from Manhattan’s northernmost end to its southern tip, some prosaic scents recurred (cigarette butts, suntan lotion, fried foods); some were singular and sublime (a delicate trail of flowers mingling with Indian curry around 34th Street); while others proved revoltingly unique (the garbage outside a nail salon). Some smells reminded me of other places, and some will forever remind me of New York.”

Lessons Learned

Potential Benefits:

- Uses smells that are unique to a particular node, street, neighborhood or city itself.

- Provides an opportunity to involve the adjoining businesses.

- Creates a multisensory experience.

Potential Issues:

- Undesirable smells: Undesirable smells can be part of the sensorial experience.

- Unintentional smells: A number of the sensorial experiences are unintentional and unprogrammed.

- Variability: Smells described in this case study are affected by seasonal and environmental factors (wind, temperature, ambient noise, cleanliness, etc.), which can impact the effectiveness of multisensory wayfinding.